@Project11 I like this post, thank you.

You bring up a good point of “mini trading depression”. Aside from all execution topics or strategies, entries or exits, the psychological impact of a “win” or a “loss” can completely change the outlook of market data.

Triggers, associations and beliefs all fall into this category. James Clear takes a real-life example of this, how a small win can result in bigger wins. It’s a good 5 min read but well worth it if you don’t know the story of British Cycling and Dave Brailsford.

The fate of British Cycling changed one day in 2003.

The organization, which was the governing body for professional cycling in Great Britain, had recently hired Dave Brailsford as its new performance director. At the time, professional cyclists in Great Britain had endured nearly one hundred years of mediocrity. Since 1908, British riders had won just a single gold medal at the Olympic Games, and they had fared even worse in cycling’s biggest race, the Tour de France. In 110 years, no British cyclist had ever won the event.

In fact, the performance of British riders had been so underwhelming that one of the top bike manufacturers in Europe refused to sell bikes to the team because they were afraid that it would hurt sales if other professionals saw the Brits using their gear.

Brailsford had been hired to put British Cycling on a new trajectory. What made him different from previous coaches was his relentless commitment to a strategy that he referred to as “the aggregation of marginal gains,” which was the philosophy of searching for a tiny margin of improvement in everything you do. Brailsford said, “The whole principle came from the idea that if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike, and then improve it by 1 percent, you will get a significant increase when you put them all together.”

Brailsford and his coaches began by making small adjustments you might expect from a professional cycling team. They redesigned the bike seats to make them more comfortable and rubbed alcohol on the tires for a better grip. They asked riders to wear electrically heated overshorts to maintain ideal muscle temperature while riding and used biofeedback sensors to monitor how each athlete responded to a particular workout. The team tested various fabrics in a wind tunnel and had their outdoor riders switch to indoor racing suits, which proved to be lighter and more aerodynamic.

But they didn’t stop there. Brailsford and his team continued to find 1 percent improvements in overlooked and unexpected areas. They tested different types of massage gels to see which one led to the fastest muscle recovery. They hired a surgeon to teach each rider the best way to wash their hands to reduce the chances of catching a cold. They determined the type of pillow and mattress that led to the best night’s sleep for each rider. They even painted the inside of the team truck white, which helped them spot little bits of dust that would normally slip by unnoticed but could degrade the performance of the finely tuned bikes.

As these and hundreds of other small improvements accumulated, the results came faster than anyone could have imagined.

Just five years after Brailsford took over, the British Cycling team dominated the road and track cycling events at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, where they won an astounding 60 percent of the gold medals available. Four years later, when the Olympic Games came to London, the Brits raised the bar as they set nine Olympic records and seven world records.

That same year, Bradley Wiggins became the first British cyclist to win the Tour de France. The next year, his teammate Chris Froome won the race, and he would go on to win again in 2015, 2016, and 2017, giving the British team five Tour de France victories in six years.

During the ten-year span from 2007 to 2017, British cyclists won 178 world championships and 66 Olympic or Paralympic gold medals and captured 5 Tour de France victories in what is widely regarded as the most successful run in cycling history.

How does this happen? How does a team of previously ordinary athletes transform into world champions with tiny changes that, at first glance, would seem to make a modest difference at best? Why do small improvements accumulate into such remarkable results, and how can you replicate this approach in your own life?

## The Aggregation of Marginal Gains

It is so easy to overestimate the importance of one defining moment and underestimate the value of making small improvements on a daily basis. Too often, we convince ourselves that massive success requires massive action. Whether it is losing weight, building a business, writing a book, winning a championship, or achieving any other goal, we put pressure on ourselves to make some earth-shattering improvement that everyone will talk about.

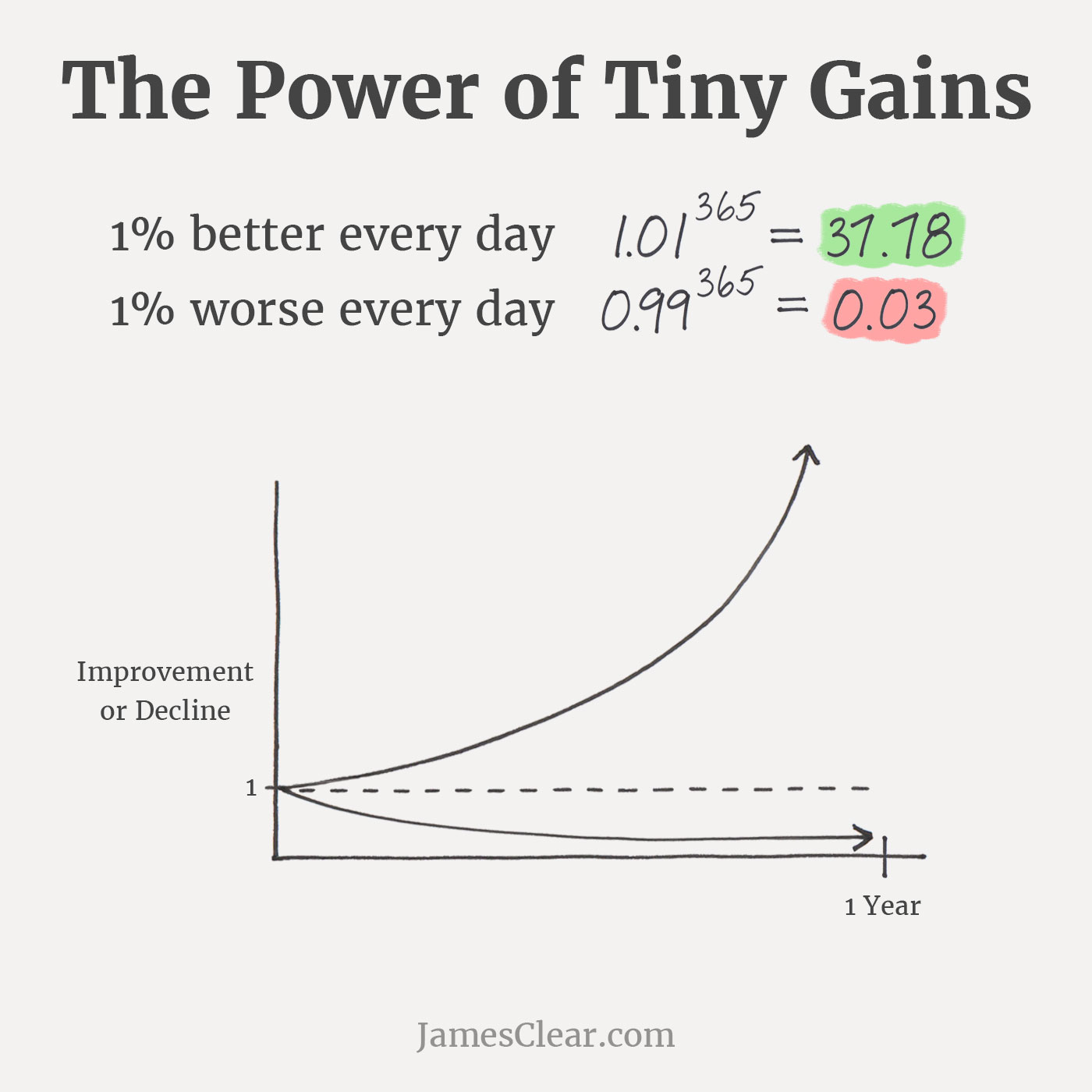

Meanwhile, improving by 1 percent isn’t particularly notable—sometimes it isn’t even noticeable —but it can be far more meaningful, especially in the long run. The difference a tiny improvement can make over time is astounding. Here’s how the math works out: if you can get 1 percent better each day for one year, you’ll end up thirty-seven times better by the time you’re done. Conversely, if you get 1 percent worse each day for one year, you’ll decline nearly down to zero. What starts as a small win or a minor setback accumulates into something much more.

Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement.

In the beginning, there is basically no difference between making a choice that is 1 percent better or 1 percent worse. (In other words, it won’t impact you very much today.) But as time goes on, these small improvements or declines compound and you suddenly find a very big gap between people who make slightly better decisions on a daily basis and those who don’t. This is why small choices don’t make much of a difference at the time, but add up over the long-term.

On a related note, this is why I love setting a schedule for important things, planning for failure, and using the “never miss twice” rule. I know that it’s not a big deal if I make a mistake or slip up on a habit every now and then. It’s the compound effect of never getting back on track that causes problems. By setting a schedule to never miss twice, you can prevent simple errors from snowballing out of control.